What Really Happened to the Neanderthals?

The Neanderthals are our closest evolutionary human cousins and for hundreds of thousands of years were much more successful at colonizing Europe than we were. Recent archaeological evidence shows that they had equal if not larger brains than Homo sapiens, developed language, tools, cared for their disabled and buried their dead—not at all the dim-witted cavemen of popular misconception.

They were stronger and better adapted to a cold post-ice age climate than we were. So why did they become extinct and we survived? The last decade has been a golden age in terms of our knowledge of Neanderthals—we have even extracted their DNA—and at last we are getting some answers.

Our shared origins

In the human evolutionary tree, Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis (commonly known as Neanderthals and named after the Neander Valley in Germany where the first specimen was found in 1856) share a common ancestor in Homo heidelbergensis. Heidelbergensis evolved in Africa but around one million years ago some of them migrated into Europe and Neanderthals evolved from them, starting to develop into a distinct species about 500,000 years ago.

Most of our evidence of heidelbergensis comes from Europe rather than Africa, and we know that they were formidable hunters (butchered bones of lions and wolves have been found from this period) and used stone handaxes. By around 250,000 years ago they had evolved into Neanderthals, their stone tools became smaller and more sophisticated, and it is this date that is generally regarded as the beginning of the time of the Neanderthals.

Given that Homo sapiens did not even reach the European continent until about 45,000 years ago this means Neanderthals were the dominant humans in Europe for at least five times longer than we have been. As recently as 100,000 years ago Neanderthals would have seemed the obvious choice to become masters of the planet.

What makes a Neanderthal?

Of course the date of 250,000 years ago as the dawn of the Neanderthals is a bit arbitrary, and as with all evolutionary processes their development was a continuous gradual process. So what really distinguishes a Neanderthal from their ancestors?

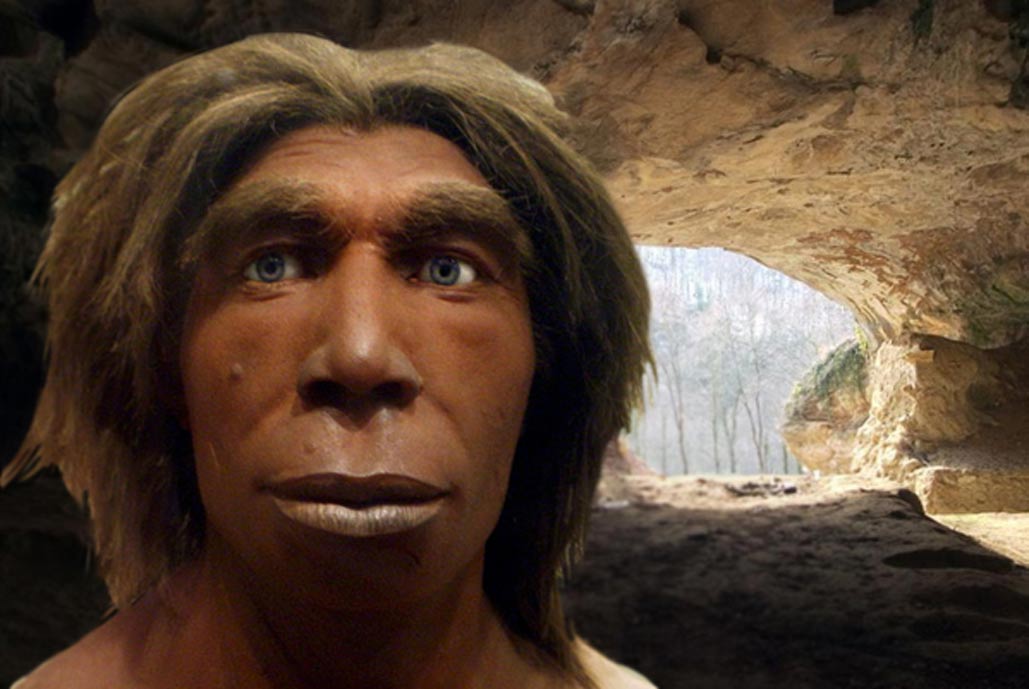

Reconstruction of Neanderthal head, Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, Washington. (Tim Evanson via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

Leading authority Dimitra Papagianni argues that it was mental ability, and specifically the ability to envisage the future and plan for it. The ability to understand their environment and plan for future events, even if it was simply to bring the right tools to skin an animal when going on a hunt. This requires a larger brain, but also the capacity for complex social communication, a concept that has been dubbed the ‘social brain hypothesis’. The idea is that they evolved a larger brain to allow more sophisticated communication and social organization, which in turn led to improved food production through more efficient hunting. Contrary to the popular image of Neanderthals as grunting dimwits who lacked fundamentally ‘human’ traits, it was their larger brains that distinguished the Neanderthals from their forebears.

Neanderthal ornamentation? White-tailed eagle talons from the Neanderthal site at Krapina, Croatia, thought to be part of a jewelry assemblage, dated to around 130,000 years ago. (Luka Mjeda via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

An example of this superior social organization comes from La Cotte de St Brelade in Jersey, one of the most impressive Neanderthal sites in Europe. This is a dramatic sea cliff, the base of which shows extensive signs of Neanderthal habitation dating from around 130,000 years ago, long before Britain became an island. Hundreds of butchered mammoth and rhinoceros bones have been found there, their sheer concentration revealing their method of slaughter: the animals were driven over the cliff to their deaths, a hunting technique which would have required significant social organization.

The Wooly Mammoth, Royal BC Museum, Victoria, British Columbia (Rob Pongsajapan, Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

At least a dozen and probably more Neanderthals would have had to work together to herd these large animals in the right direction, anticipating in advance what to do if they did not do so, and choreograph and execute a complex series of moves to get them to the exact right spot of the cliff. Even if they only killed a single animal this way they would then need to butcher and divide the carcass between their social group. All of this is exactly how north American Indians killed big game as recently as 150 years ago.

New technology: example of a Levallois point, a technique developed by Neanderthals. (Sharon Gonen via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Technologically, Neanderthals were innovators too. They had inherited what is unquestionably the most successful tool of all time, the stone handaxe, which dates to at least 1.76 million years ago when the first example we know about was made by Homo erectus on the banks of Lake Turkana in Africa. What is surprising is that they were then used without improvement for well over a million years until around 400,000 years ago, when the Neanderthals developed the technique of knapping smaller, sharper flakes off a central core.

Reproduction of what Neanderthals may have looked like, Neanderthal Museum, Krapina, Croatia. (Erich Ferdinand, Flickr/CC BY 2.0)

Known as the Levallois technique, this meant that instead of carrying a single heavy axe, they could instead carry a flint core and knock off fresh flakes when needed. This in turn meant that they could travel further which in turn improved their chances of hunting migratory animals, as well as allowing them to meet more humans, which improved their opportunities for finding sexual partners. It is interesting that such blade production was long thought to be unique to Homo sapiens, but we now know that Neanderthals were also producing them at an early stage.

Physically, Neanderthals were shorter, stockier and considerably more muscular than modern humans. To our eye they would probably have been quite ugly, with prominent bone ridges above the eyes, big flat noses, jutting faces and no chins. Their heads were large and flat, with short arms and legs and barrel chests.

Could they pass unnoticed among us? Reconstruction of a Neanderthal man in a modern suit, at the Neanderthal Museum, Krapina, Croatia. (Einsamer Schütze via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

There were some differences from our ancestors when it came to diet however. We know from the analysis of butchered bones as well as the ratio of certain isotopes in ancient bones and teeth that Neanderthals’ diet consisted almost entirely of meat, mainly large animals such as woolly mammoth but also bison, reindeer and horse. In fact, about 80 percent of Neanderthals’ nutrition was from meat, about 20 percent from vegetation, a small amount from shellfish in coastal locations, and they did not eat fish. Homo sapiens had a more balanced diet and they ate a lot of fish where it was available. As it turns out, these differences may have been more significant than they first appear.

Did Neanderthals and modern humans coexist?

Two questions which palaeoanthropologists have been asking for a long time are whether Neanderthals and homo sapiens coexisted, and if so, whether they interbred. Is there any Neanderthal in us?

These questions have been surprisingly hard to answer. The home territory for Neanderthals for a very long time was Europe, and the two species did not come into direct contact on this continent until modern humans entered Europe around 45,000 years ago. Around 130,000 years ago they almost met – we know that at that time, at the end of a long and intense glacial period, Neanderthals were occupying the land north of the Strait of Gibraltar and Homo sapiens were to be found just to the south in Morocco and elsewhere in North Africa. But despite the fact that the Strait is only 9 miles wide at its narrowest point (it may have been a bit wider back then) there is no evidence they were aware of one another’s presence.

The first hard evidence for the two species meeting actually comes from northern Israel 50,000 years later. In the warm period starting around 130,000 years ago, known as the Eemian interglacial, Neanderthals started to expand their range out of western Europe and towards the east. By around 60,000 to 50,000 years ago they had spread along the Mediterranean and entered northern Israel, where Homo sapiens had been living since roughly 100,000 years ago. This was the first time the two species had met since they had separated from their common ancestor Homo heidelbergensis half a million years earlier. There is however little evidence of confrontation or indeed interbreeding between the two groups.

The Neanderthal’s territory – where Neanderthal remains have been found, and maximum extend of ice sheet during Last Glacial Maximum. (Maximilian Dörrbecker via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

By this time Homo sapiens was well on the way to conquering the planet, spreading east across Asia towards China and Australia. Neanderthals spread east too, but in much smaller numbers, and would have met our ancestors everywhere they went. Israel is about 4,000 km (2485 miles) from Gibraltar, and they have been found a further 1,000 km (621 miles) to the east in Iraqi Kurdistan, and another 2,000 km (1242 miles) still in Uzbekistan where a single Neanderthal child burial has been found. The furthest east they are known to have reached is the Altai Republic of Siberia, bordering Mongolia, yet another 1,500 km (932 miles).

The Neanderthal in all of us

As for the salacious question of whether our ancestors had sex with Neanderthals, thanks to the wonders of DNA analysis we now know that they did, but not much. In 2010 a draft Neanderthal genome was published based on samples extracted from bones of three individuals from Croatia. Whilst the genome did not show any sign of DNA from Homo sapiens, it did show that our DNA contains a small amount of Neanderthal DNA, around 2 percent for modern human populations not indigenous to Africa.

Subsequent work on more DNA samples from both Neanderthals and early modern humans from Siberia has shown there were most probably two distinct interbreeding events—one prior to around 100,000 years ago and another between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago. But the very small amounts involved show that such events were far from common, and certainly the reason that the Neanderthals disappeared could not have been that they simply merged with Homo sapiens.

DNA analysis of Neanderthal and early humans is an active area of research and new discoveries are being made all the time. For example, we now know that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens share genes for green eyes and red hair, presumably something that both species inherited from our common ancestor Homo heidelbergensis. It has been shown that Neanderthals evolved genes for pale skin independently from modern humans, perhaps as a result of living mainly in northern Europe, and that they also share a gene called FOXP2 with us, which is related to motor skills and coordination, and believed to be necessary for the development of speech.

Clues to the fate of the Neanderthals also comes from their DNA. It has been shown that by 50,000 years ago their genetic diversity was contracting, that they were suffering from inbreeding. This is usually found in small groups of individuals living in relative isolation, in turn limiting the diversity of sexual partners. In all probability this was a consequence, not a cause of a dwindling population, as the population became more geographically spread out and isolated.

The beginning of the end for Neanderthals

So despite being the dominant human species in Europe since at least 250,000 years ago, by 50,000 years ago we find them mysteriously in decline. Were they overly dependent on specific animals for food which died out, such as the mammoth? Was it the result of a change in climate? Did Homo sapiens drive them off or kill them?

Of these possible causes there is little evidence that Homo sapiens specifically targeted or wiped out the Neanderthals. For a start we now know that they had been in decline for several thousand years before our ancestors entered Europe. Although there are a few sites where Neanderthal bones show signs of butchery, and plenty where they show injuries consistent with fighting, there is no evidence of Homo sapiens attacking Neanderthals on a widespread basis.

Around 55,000 years ago the European climate started to cool, and by 37,000 years ago the northern hemisphere entered another glacial period with an ice sheet centered on Norway, spreading across northern Europe as far as Britain to the west and the Urals to the east, perhaps the northern quarter of the Neanderthals territory. By the time the Last Glacial Maximum reached its peak around 26,000 years ago, the Neanderthals were extinct in Europe. Could the colder climate explain their demise?

Although only a small part of Europe was actually covered by ice, the glacial period had a major impact on climate throughout Europe. Specifically, it led to an expansion of the amount of open steppe and grasslands at the expense of forests, and with it a change in the animal species living there. There is little doubt that this played against the Neanderthals, who preferred warmer more sheltered territory favorable to their style of hunting of ambushing or trapping their prey, rather than the long endurance chase.

Despite the fact that Homo sapiens had only arrived in Europe relatively recently, the change in climate favored the more agile Homo sapiens, who were more successful in chasing and hunting game on the open grasslands. The result was that Neanderthals contracted to their preferred habitat just at the time Homo sapiens were expanding their territory onto the open steppe.

Iberia: the final refuge?

Before long the Neanderthals found themselves pushed back by shortage of suitable habitats and prey to the southern corners of the continent – the Iberian Peninsula, Crimea, and the southern Balkans. These areas were most likely their final refuges in Europe, although there is quite a bit of debate about exactly when this happened, largely because the period in question (around 40,000 to 50,000 years ago) is at the very limit of the radiocarbon dating method.

A recent major study of forty Neanderthal sites from Russia to Spain concluded with 95 percent probability that they died out between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago, the exact date varying with geographical region. They also found that modern humans entered Europe between 2,600 to 5,400 years prior to the disappearance of the Neanderthals, which they regard as sufficient time for the transmission of cultural behavior (such as styles of stone axes) and possible interbreeding between the two groups.

Hints of a cultural side: a Neanderthal ‘hashtag’ rock carving from Gorham’;s Cave, Gibraltar, a classical Neanderthal site. (Stewart Finlayson, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

There are however some sites that appear to contradict this, notably the burial of a Homo sapiens child in Portugal (known as the Lapedo child) dated to 24,500 years ago, which some anthropologists argue shows significant Neanderthal traits, and also two Neanderthal skulls from Vindija in Croatia which have been dated to between 29,000 and 28,000 years ago.

Vindija Cave, Croatia, location of the last Neanderthal dated to 29,000 to 28,000 years BP. (Tomislav Kranjcic via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

So for now the exact date of the last Neanderthal remains open, as does the question of whether they went extinct as a separate species, or simply merged with Homo sapiens through interbreeding. But there is little doubt about their achievements as the dominant human species in Europe for 200,000 years, and the more we learn about them the more ‘human’ they become.

David Millar is a science writer and author of ‘Beyond Dubai: Seeking Lost Cities in the Emirates’.

Featured image: Deriv;Reconstruction of a Neanderthal, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany (CC BY-SA 3.0), Vindija cave near Varazdin in Croatia (CC BY-SA 2.0)

References

The Neanderthals Rediscovered: How Modern Science is Rewriting their Story, Dimitra Papagianni & Michael Morse, Thames & Hudson, 2015

The Humans Who Went Extinct: Why Neanderthals Died Out and we Survived, Clive Finlayson, Oxford University Press, 2009

Lone Survivors: How We Came to be The Only Humans on Earth, Chris Stringer, St Martins Griffin, 2012

The Last Neanderthal: The Rise, Success, and Mysterious Extinction of our Closest Human Relatives, Ian Tattersall, Westview Press, 1999

Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins, Ian Tattersall, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012

The timing and spatiotemporal patterning of Neanderthal disappearance, T. Higham, et al, Nature, 512, 306-9, 2014