Medicine Macabre: The Healing Magic and High Value of Human Fat

What now seems macabre and grisly to many, harvesting parts of the freshly dead human body for use in healing was an old, traditional practice by doctors who claimed it was excellent in treating and curing a host of ailments.

Between skull powder medicine and fresh blood concoctions, ancient doctors working in the field of so-called ‘corpse medicine’ let no part of a dead body go to waste. Not a remedy for the squeamish perhaps, ancient and early modern healers extolled the virtues of human fat and its healing properties.

Pharmacopoeias, or ancient medical texts, listed human fat as an important component of ointments and salves in Europe since the 16th century. Besides fat from the likes of beavers, bears, snakes, cats and more, human fat was included in old medicine recipes.

A replica of human fat. The natural color is yellow. (Public Domain)

Human fat is not necessarily an ingredient that has ever been easy to come by, but when acquired it was judiciously and sparingly used to treat ailments and mend the sick (or rather, those who could afford the high-priced fat treatments at apothecaries, the early precursors to pharmacies.)

Often in this cannibalistic medicine, the key to treating a specific illness was to match the medicine with the problem area: ground skull powder was used for headaches, blood was ingested for blood diseases, fat was rubbed on the body, etc.

Two apothecary vessels with inscription AXUNG. HOMINIS for human fat, approx. 17th or 18th century. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Not only was it believed that fat, blood, or other body parts and fluids could cure illness, but consuming part of the deceased meant receiving its spirit, thus improving overall health. As well, the fresher the ingredients, the better. By using the corpse medicine from the recently deceased, it was believed you gained the strength, vitality, and youthful health of the ‘donor’.

Leonardo da Vinci wrote, “We preserve our life with the death of others. In a dead thing insensate life remains which, when it is reunited with the stomachs of the living, regains sensitive and intellectual life.”

Dissection of a cadaver, 15th century painting. (Public Domain)

Ancient Remedies

Such treatments were popular from the Renaissance to the Victorian era, reaching heights in the 16th and 17th centuries. However, ancient civilizations and traditional medicine certainly held with these beliefs. Romans drank the blood of gladiators to absorb their vitality and strength, as well as to cure epilepsy. Babylonians were counselled to sleep with human skulls to stave off teeth-grinding at night. Kissing or even licking the skull was thought to ensure successful treatment.

Human fat (Axungia hominis in Latin), when rubbed onto the skin like a balm, was said to help ease joint and muscle pain such as gout or arthritis. Fat was blended into ointments and slathered on bandages to be applied to an open wound. It was even used to ease toothache—though it may be difficult in modern times to imagine voluntarily putting human fat in the mouth.

Glass vessel with inscription with content and "Adeps Humani". The object is a part of the pharmacists collection in Hamburg Museum, Germany. (Public Domain)

Executioners Made a Killing on the Fat of the Condemned

Where fat was obtained was also an unpleasant idea. Up into the 19th century in Europe, fat was a highly sought-after commodity, but it was always hard to come by unless you had a ready source, which executioners invariably did. This "Armsünderfett" or "Armsünderschmalz" (German for “fat or grease from poor executed sinners”) was collected from the bodies of the freshly dead and then sold. It was a good way for executioners to make money, especially as theirs was an occupation that made them social outcasts for the most part.

The execution of Pirates in Hamburg in 1573. Executions were a handy source of human fat. (Public Domain)

The poor who could not afford the expensive compounds at the apothecary could attend executions to pay the executioner for fat, a cup of steaming, fresh blood, or various other unpleasant human-based medicinal ingredients.

In this the executioner played two roles: that of death-bringer, and also of trusted healer.

Richard Sugg, author of Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians said, “The executioner was considered a big healer in Germanic countries. He was a social leper with almost magical powers.”

Though publically shunned for their dirty work, early modern German executioners were also frequently visited for their medical expertise. Citizens of stature such as social elite or guildsmen would visit the executioner/healer for his wares and such meetings were not seen as inappropriate or dishonorable.

From Kathy Stuart’s Defiled Trades and Social Outcasts: Honor and Ritual Pollution in Early Modern Germany:

Executioner medicine presents a number of incongruities. First, the executioner's symbolic role as one who was licensed to kill was offset by his role as a healer. The very man whose official function was to kill and maim spent much of his time ‘off duty’ practicing medicine. Second, executioner medicine demonstrates the complexity and fluidity of the social boundary separating honorable estates from ‘dishonorable people’ and the fundamental ambivalence artisans felt as they negotiated this boundary. Executioners were not polluting all the time. It was completely unproblematic to consult them in medical matters. Patients left the executioner's home after close personal and often physical contact with the executioner with their honor intact.

The human fat was mixed with perfumed oils, beer, or other fat-soluble substances.

Evil Monsters That Prey on Fleshy Victims

In folklore of the Andes region of South America, an evil monster, the Pishtaco (or Lik’ichiri), is often imagined in the form of a white, European bearded man who hunts down innocent Indians for their body fat. The Pishtaco was believed to devour the victim’s fat, or cut up their body parts and fry them to sell as Chicharrón—delicious pork belly appetizers.

A strange tale to be sure, but not necessarily surprising, as this myth is said to date to the Spanish conquest of South America.

Body fat is traditionally prized in the Andes region. Visible human body fat was taken as a sign of good health, beauty, and strength. Loss of body fat and extreme thinness is seen as a sign of illness. The deity Viracocha, with a name meaning “sea of fat” represents these ideals.

The deity Viracocha. (Public Domain)

It is said the conquistadores treated their own wounds with the fat of dead humans, horrifying the native South Americans. This societal view on human fat later raised fears about missionaries, as Andean aboriginals believed them to be the dangerous pishtacos on the hunt for fat so they might oil their church bells with them, making them especially loud and irresistible. It was even thought the bell’s sound would vary according to the victim.

Even now some still believe that modern equipment or machinery needs a squirt of the naturally-magical human fat to ‘christen’ it, or to get it to work smoothly.

Indeed, some international aid and health programs to Peru and Bolivia in the 1960’s were reported to have been hampered by local beliefs in the Pishtaco. It was feared that the people were being fed by outsiders, and weighed and measured to be later exploited for their fat. In modern incarnations of the urban legend, the fat is stolen to be sold to (often North American) corporations, usually cosmetic and pharmaceutical companies.

A gruesome depiction of Pichtacos at work. People are harvested for their fat, and bells ring on their stands. (Public Domain)

In Dark Tales in Latin America, writer Benjamin Radford describes the Lik’ichiri lore:

“[…] the lik'ichiri attacks people as they sleep on the altiplano, the fat thief cutting long, thin slits in the victims' sides and removing their fat. The extraction is painless, and the wound heals promptly without the victim being any the wiser. While at first a lik'ichiri attack might appear to be a cheap and efficient method of weight loss, according to the legend, the eventual results are much graver: unless treated promptly, the victim will die. Treatments include the clandestine administration of a mixture called achacachi.”

To ward off Lik’ichiri attacks, it is advised to eat plenty of garlic in order to dilute the fat, or to render it unusable to the fat sucker. Also, it is deemed prudent to not be out wandering the streets at night to avoid becoming the next victim.

Fat Sellers and Serial Killers

Similarly in Spain, mythical Sacamentacas, or “Fat Extractors,” were believed to be bogeymen disguised as beggars who would steal children away, requiring to drink the blood of babies to survive. It was said they also killed to gain precious human fat to feed upon. Anthropologists believe the practice of blood donation gave rise, or at least support, to this old myth.

Known also as Mantequero, or “Fat Seller, Fat Maker”, this folkloric monster roamed deserted areas, looking for victims so he could feed on manteca (human fat). Mantequeros were said to be very thin (unless they’d recently fed), and would emit a high pitched scream if ever captured.

Not unlike the stories of the Countess Bathory, bathing in the blood of virgins to absorb her victims’ youth, urban legends had it that the mantequero was a rich, evil old man who needed blood and fat to rejuvenate—an analogy of elites feeding on the lower classes, harvesting them for their youth and spirit.

Like other truths that spur legends, a few of these fearsome creatures were found to be all too real.

The very first documented serial killer in Spain, a travelling salesman named Manuel Blanco Romasanta (1809 -1863) was accused of killing women and children, removing the fat from his many victims, and selling it for gold. It was said he made high-quality soap with the fat. During his trial he admitted to killing at least thirteen people, but claimed he did it because he was cursed with lycanthropy (the ability to shapeshift into a wolf or werewolf), and couldn’t control himself.

The sketched portrait of Manuel Blanco Romasanta, a real life “Fat Extractor”. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Stories of this ‘real-life’ Sacamentaca were used to scare children into behaving, and remaining close to home at night.

Fat Injections and Human Soap

Human fat was acquired, prepared and sold under the revealing name Humanol in the late 19th century. This sterile liquid was injected into patients in Germany, with the belief that it reduced or eliminated scars, and disinfected and healed wounds. By the 1920’s people stopped these human fat treatments due to low success rates and growing incidences of fat embolisms, or the lodging of a fat glob in the bloodstream—a dangerous medical situation generally only occurring as a result of fractured bones or bad burns that can end in heart attack or death.

Remaining samples of Humanol in small 5.5 ml vials to be used in injections. Germany, early 20th century. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

During World War II it was rumored human fat was used in specialty cleaning agents and soaps, made to order for the director of the Danzig Anatomical Institute, to be used to clean and sanitize autopsy rooms. Various reports point to the Stutthof concentration camp, Danzig Municipal Jail, and a psychiatric hospital as an alleged source of human fats for soap, but later investigations suggested the evidence for human-fat-soap is very thin, and it was simply a British urban legend dating to World War I. These tales of people being boiled into soap served to intimidate and frighten Jews and other groups during World War II. Some were reportedly told by the Gestapo, “We’ll make soap out of you.”

Blocks of soap. (Flickr/CC BY-ND 2.0)

Scholars of the Holocaust admit that a few bars of experimental soap may have been made with human fats at Stutthof, but that it was never done on a mass scale.

The use of human fat ointments and beauty products are believed to have continued into the 1960’s, in the form of wrinkle creams. These creams were made from human fat gathered by midwives and doctors from human placentas after labor. This was short lived, and animal products were used instead.

Apothecary drug jars used to store animal fat (horse and badger) for use in ointments, Italy, 1585. (Wellcome Trust/CC BY-4.0)

While popular culture keeps alive the idea of “fat theft” for soaps and cosmetics, the truth lies not far away.

To this day human fat has its uses. After being voluntarily removed from the client’s body in a process called “fat banking” or “Lipobanking”, tissue and fat is stored to be used for future cosmetic purposes. The fat is later injected back into the original donor to purportedly plump and tighten the skin, diminish wrinkles, and enlarge breasts. This procedure comes with a high price-tag, in an echo of the expensive 16th and 17th century apothecary treatments. These human fat treatments are seen as less dangerous than chemical substances and filler, and perhaps even beneficial.

Plastic surgeon Dr. Jeffrey Hartog says,

Fat banking takes this [procedure] to a whole new level.

We put the patient to sleep once. Do the lipo. Get the fat out once and have as much as we need for later injections.

Experts caution that frozen fat doesn’t hold up as well, so the fresher the fat, the better.

These modern uses of human fat as cure-alls show that times may have changed, but people clearly haven’t.

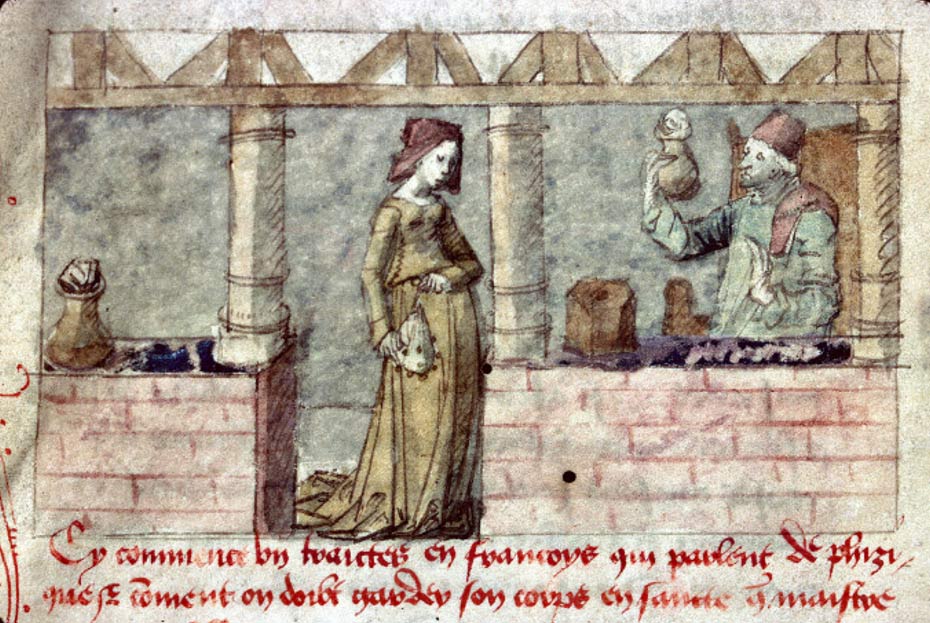

Featured image: A woman seeks healing compounds at a French apothecary, 15th century illustration. (Public Domain)

References

Dolan, Maria. 2012. “The Gruesome History of Eating Corpses as Medicine” Smithsonian.com [Online] Available here.

Andrews, Evan, 2014. “7 Unusual Ancient Medical Techniques.” History.com [Online] Available at: http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/7-unusual-ancient-medical-techniques

Radford, Benjamin. 2005. “Dark Tales in Latin America” [PDF] Available here.

Sugg, Richard. 2011. “Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: the History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians”. Published by Routledge (Aug. 9, 2011)

Stuart, Kathy. 2009. “Honor and Ritual Pollution in Early Modern Germany” Cambridge.org [Online] Available at: http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9780511496967

Real Self. “Fatbanking: Freezing Liposuction Fat for Future Use”. 2012. RealSelf.com [Online] Available at: http://www.realself.com/blog/freeze-your-fat-for-future