Fire and Sword: Ferocious and Deadly Thermal Weapons set the Ancient World Ablaze

One only had to witness cities devoured by flames, see fleets of ships sinking, their sails ablaze, or behold screaming victims doused in boiling pitch to know the deadly efficacy of ancient thermal weapons.

Warfare was brutal, but effective, in the ancient world, between conventional arms of sword, bow and shield, to the invisible but deadly poisons and biological weapons. But perhaps none were as instantly terrifying and widely destructive as thermal weaponry.

Early thermal weapons were used inventively in warfare during the classical and medieval periods (eighth century BC to mid-16th century AD) around the globe. These substances or devices used heat, whether from flame or burning action, to attack the enemy armies, civilians, fortifications, and infrastructure. Fire was the easiest way of destroying land and people, and could be done quickly and by small forces or raiding parties, making it a fundamental strategy in war. It was particularly useful in inspiring fear and confusion among the enemy. Fire was used in defense, as “scorched earth” tactics involved setting one’s own land and homes on fire and reducing them to ashes to deprive the enemy resources: buildings, food, or treasure.

The most common and basic thermal weapons available to the ancient warriors were: fire, wood, boiling water, hot sand, hot pitch (bitumen or resin), oil and animal fats, quicklime and sulfur, and even excrement. These items could be heated or ignited, launched with arrows, or poured or thrown from heights. The aim of the thermal weapons was not to explode but to inflict burns or collapse structures due to the spreading fire.

Behold from your walls the lands laid waste with fire and sword, booty driven off, the houses set on fire in every direction and smoking.

-Titus Livius Patavinus (Livy), The History of Rome

Flaming Arrows

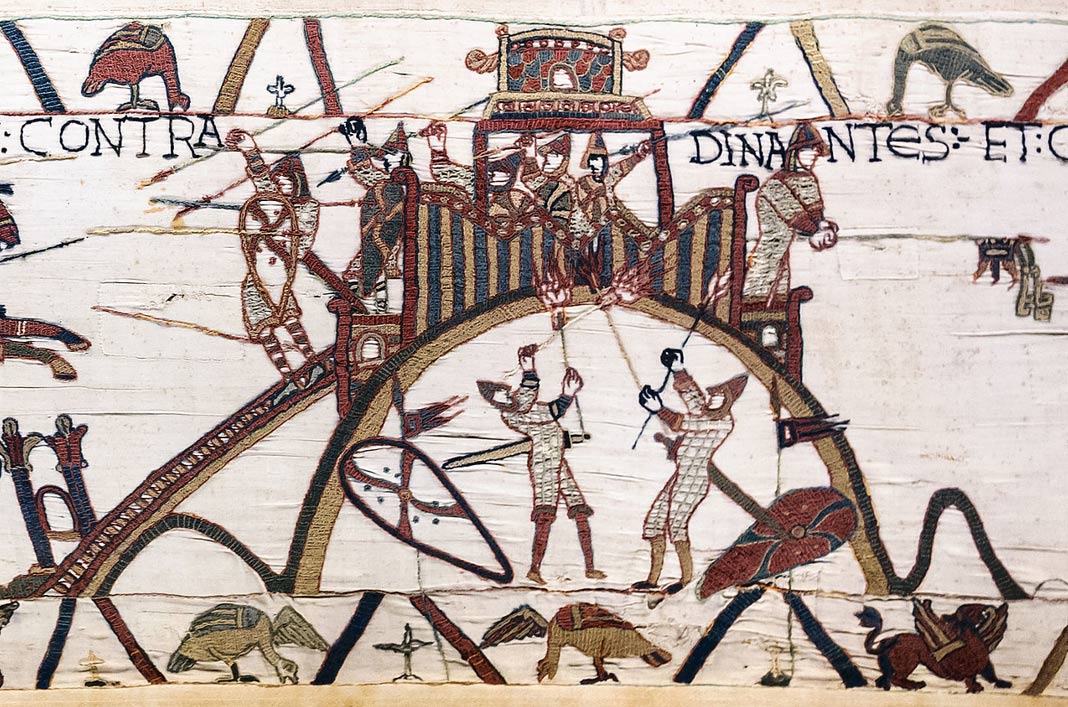

The Bayeux Tapestry contains one of the earliest representations of a castle. It depicts attackers of Château de Dinan in France using fire, one of the threats to wooden castles. Public Domain

The earliest form of thermal weapons were likely the simplest; burning sticks and lit torches. Piling pitch- or resin-coated wood against a building easily triggered an inferno. Flaming missiles, such as burning arrows, came next. So easy and successful were such tactics, that some armies created “fire troops”, and Muslim armies had fire archers called “naffatin”.

Sometimes this fire-raising could slip out of control, hampering or causing disaster for those who set them.

Boiling Oil

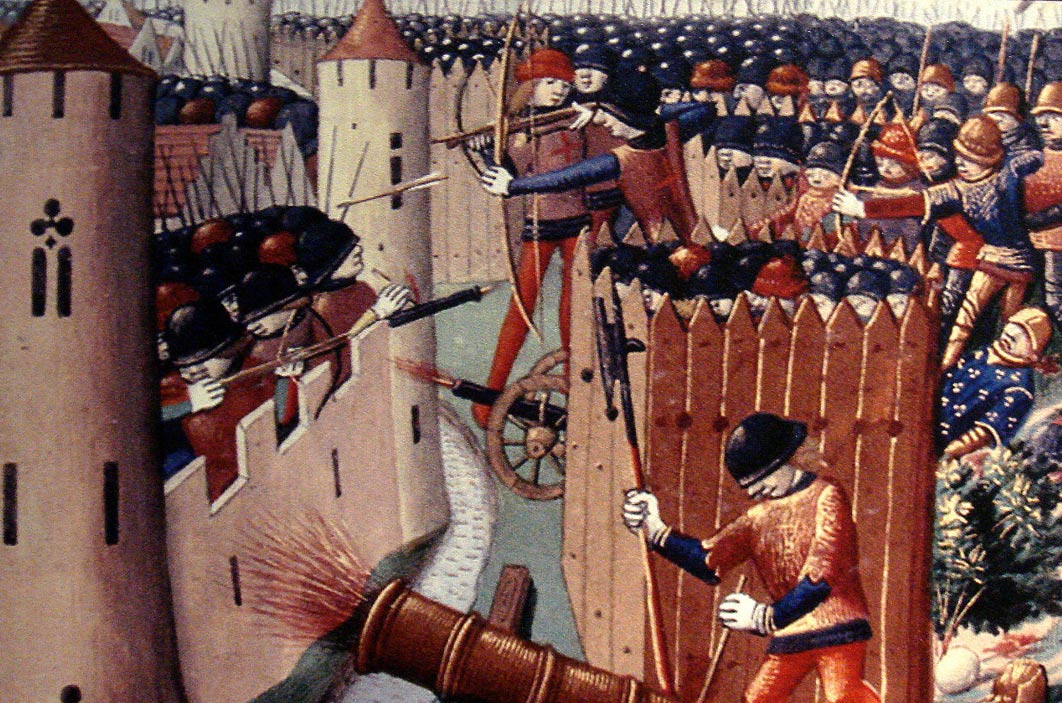

A depiction of the Siege of Orléans, 1429. Public Domain

The image of beleaguered castle defenders emptying large vats of boiling oil down onto their attackers is a common one. HistoryExtra.com writes that in 67 AD the Jewish defenders of Yodfat poured scalding oil onto their Roman besiegers, and it’s recorded as being used, alongside hot coals and quicklime, by the French against the English attackers at the siege of Orleans in 1428. However, oil and fat were valuable, and may have been too scarce to be used in great quantities.

Alexander the Great and his armies suffered a thermal weapon attack at the siege of Tyre, as chronicled Quintus Curtius Rufus in his Historia Alexandri Magni: “Furthermore, they [the Tyrians] would heat bronze shields in a blazing fire, fill them with hot sand and boiling excrement and suddenly hurl them from the walls. None of their deterrents aroused greater fear than this. The hot sand would make its way between the breastplate and the body; there was no way to shake it out and it would burn through whatever it touched. The soldiers would throw away their weapons, tear off all their protective clothing and thus expose themselves to wounds without being able to retaliate.”

Engines and Ships of War

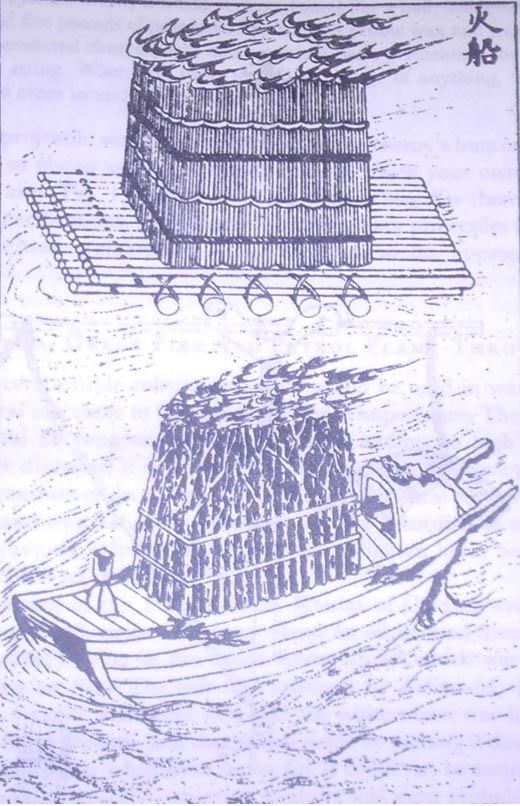

Chinese “fire ships” from the Wujing Zongyao military manuscript, 1044, Song Dynasty. Public Domain

Fire ships were used by many armies at various time. They consisted of floating vessels filled with brush, pitch, cedar torches, straw, powders and other combustibles. These were piloted to their target and then set alight, as the crew abandoned ship quickly.

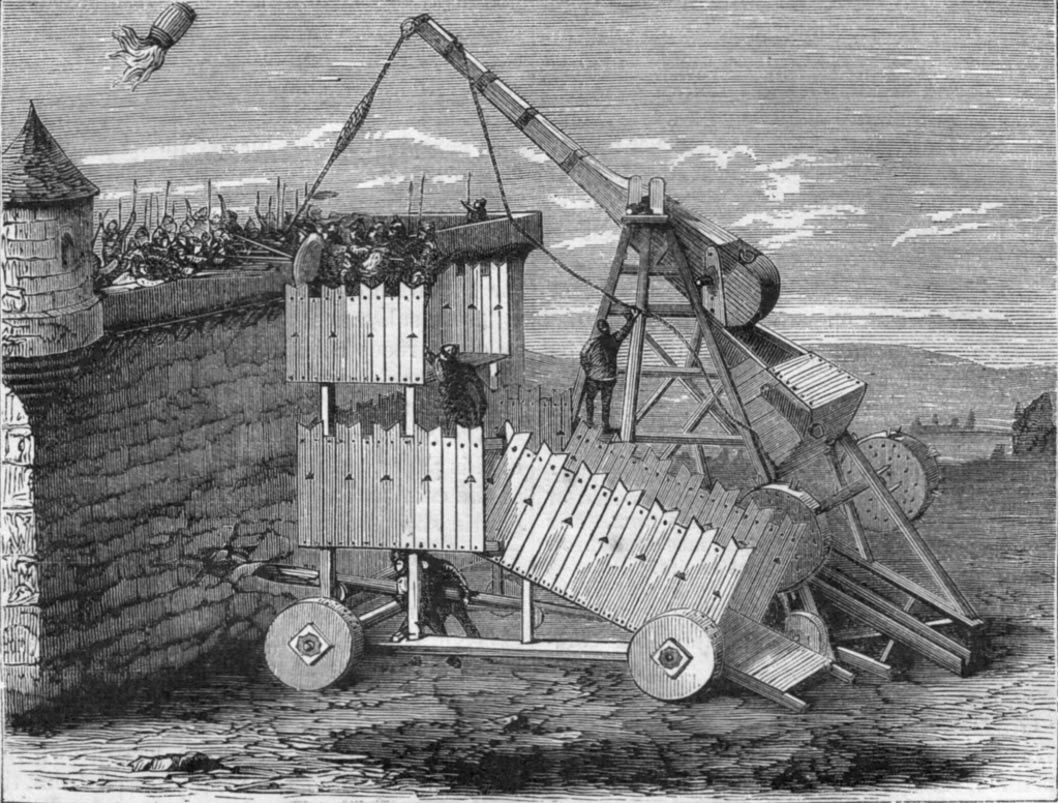

Clever engineering birthed siege engines such as the throwing machine. These wooden structures—ballista, trebuchet, catapult—could fling or shoot missiles at fortresses, castles or cities. Barrels or breakable clay or glass pots were filled with pitch, Greek Fire or other flammable mixtures. These types of remote attacks were very effective. Raining fire on wooden buildings set everything ablaze and stone walls were susceptible to high temperatures, and would crack and collapse.

Engraving showing a 13th-century trebuchet launching an incendiary missile. Public Domain

Greek Fire

Image from an illuminated manuscript, the Madrid Skylitzes, showing Greek Fire in use against the fleet of the rebel Thomas the Slav. The caption above the left ship reads, “the fleet of the Romans setting ablaze the fleet of the enemies.” Public Domain

The Byzantine Empire wielded an effective weapon dubbed “Greek Fire”. The notorious thermal weapon was a mysterious substance launched in clay pots via catapult, or fired at the enemy by the use of tubes mounted on ships. Also described as “sea fire” or “sticky fire”, the weaponized substance, like modern napalm, would adhere to anything it was fired at, and burn tenaciously, immolating wooden ships, buildings, and human skin. Water could not extinguish it. In fact, some historians believe water ignited it.

What made the Byzantine use of this burning thermal weapon notable was their use of pressurized nozzles to spray the enemy with liquid fire much like modern flamethrowers—a terrifying sight, and undoubtedly a horrific death. Greek fire was said to burn on water, and could only be extinguished with sand, vinegar or urine.

This incredible substance remains a mysterious chemical mixture, the recipe to which has not been unlocked by modern experts.

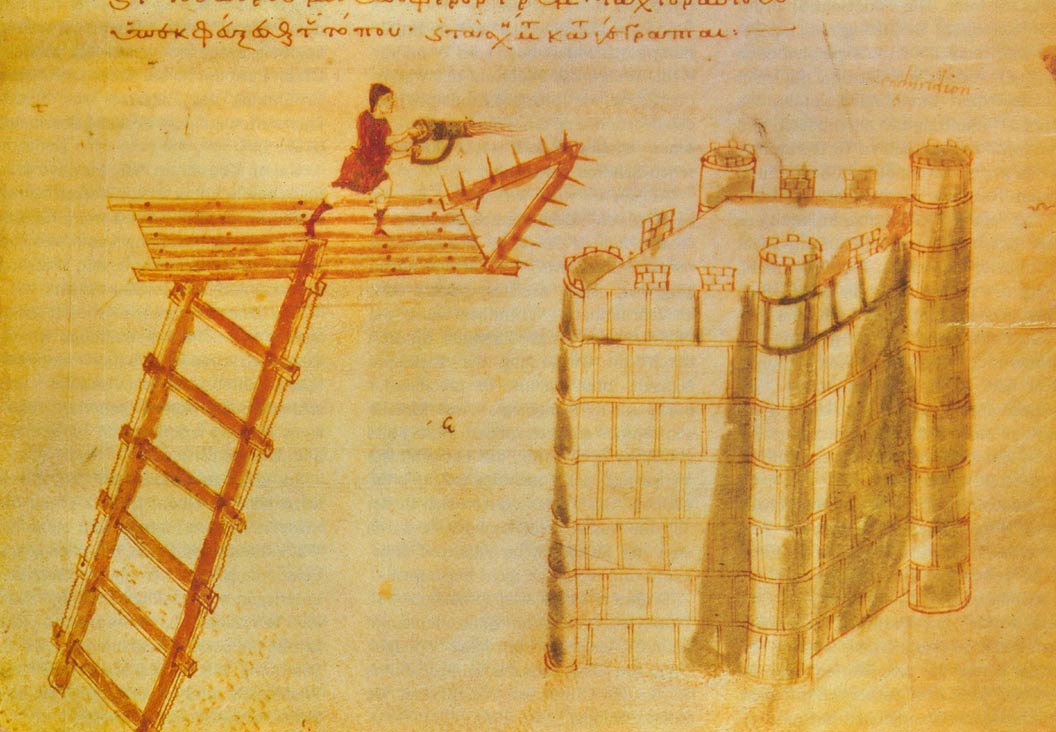

Use of a cheirosiphōn ("hand-siphōn"), a portable flamethrower, used from atop a flying bridge against a castle. Public Domain

Burning Glass

Harnessing the sun’s powerful rays with a focusing glass, crystal or mirror is an ancient technology, and was said to have been employed by the renowned mathematician Archimedes to smite the enemies of Syracuse. In 212 BC, Syracuse was under attack by the Romans, led by Marcus Claudius Marcellus.

It was recorded by the author Lucian (second century AD) that during this siege Archimedes destroyed enemy ships with fire. Later, it was said burning glasses— giant silver shields— were the thermal weapon that achieved this. Now dubbed the “Archimedes heat ray”, legend has it that silver surfaces or mirrors reflected and focused the powerful sun rays on the approaching Roman fleet, causing the ships to catch fire and sink or flee. This only delayed the ultimate Roman victory, however, as eventually the city was taken, and Archimedes was killed.

A depiction of how Archimedes may have set the Roman ships on fire with the help of parabolic mirrors. (Wikimedia Commons)

Ancient Thermonuclear War

Ancient Hindu texts describe great battles taking place and an unknown weapon that causes great destruction. A manuscript illustration of the battle of Kurukshetra, recorded in the Mahabharata. Public Domain

There are those who look to the ancient records and find mysterious references to advanced thermal weaponry that may have been used long before burning sticks and crude firebombs.

The ancient Sanskrit text, The Bhagavad Gita, reportedly describes a profound global disaster caused by an “unknown weapon, a ray of iron,” which some researchers consider a reference to the existence and use of devastating thermal weapons long before our advanced civilization.

In the ancient Hindu text Mahabharata from 400 BC, the weapon was described as, “a single projectile charged with all the power of the Universe. An incandescent column of smoke and flame as bright as the thousand suns Rose in all its splendour…”

These descriptions seemingly echo what we know of our advanced nuclear explosions. In addition, fused glass fragments created by incredibly high heats are found throughout deserts around the globe, remarkably the same as those found at test sites, as created by the effects of nuclear explosions.

Were the references to large-scale disaster simply allegories, or evidence of a thermonuclear war in the ancient past?

With the advent of gunpowder in the ninth century in China, thermal and explosive projectile weapons became more sophisticated and effective, and the early fire-based techniques were used less frequently. However, modern weapons such as flame throwers, napalm, and heat rays stem directly from early thermal inventions.

Though technologies have changed, the wars still rage, and nothing continues to terrify humanity at its core quite like the sight, sound and smell of a raging inferno.

Featured image: The Siege and Destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans Under the Command of Titus, A.D. 70, by David Roberts (1850), shows the city burning. Public Domain

References

Quintus Curtius Rufus. Translation John Yardley, 1984, 2001. “The History of Alexander.” Penguin UK, 2005 [Online] Available here.

GlobalSecurity.org, 2015. “Military: Incendiary Weapons – History.” [Online] Available at: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/munitions/incendiary-history.htm

Neal, Leslie Maryann, 2015. “Greek Fire: One of History’s Best-Kept Military Secrets” All That is Interesting [Online] Available at: http://all-that-is-interesting.com/greek-fire

Wilkes, Jonny, 2014. “Did defenders of castles really pour boiling oil down on attackers?” History Extra [Online] Available here.

Vintini, Leonardo, 2013. “Desert Glass Formed by Ancient Atomic Bombs?” Epoch Times [Online] Available http://www.theepochtimes.com/n3/23630-ancient-atomic-bombs/